TSUKUBA FUTURE

#010 Archaeological Science Highlights

Associate Professor TANIGUCHI Yoko, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences

In March 2008, an important discovery rocked the worlds of people involved in the field of art history. Until then, it had been believed that oil painting techniques had originated in Europe. However, that honor has now been stripped away from Europe, as it now seems highly likely that the true origins can be traced back to Asia. In addition, there has been a secondary shock in the form of the suggestion that the subjects first drawn as oil paintings were not images from Christianity, but images from Buddhism.

Large portions of the Buddhas of Bamiyan in Afghanistan, the famously massive stone Buddha statues, were destroyed at the hands of the Islamic fundamentalist forces of the Taliban. Brilliantly colored Buddhist murals were a famous part of this site, but more than 80% of them have been destroyed. A project to preserve and restore the destroyed ruins was launched under the leadership of UNESCO in 2003. As a member of the National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Tokyo, Prof. Taniguchi joined this project while it was already in progress. Prof. Taniguchi is in charge of the preservation and restoration of the murals. To determine the most effective preservation and restoration methods, researchers need to know what materials and methods were used when the murals were first created. This information is also essential for cleaning contaminants off the surface without damaging the murals themselves.

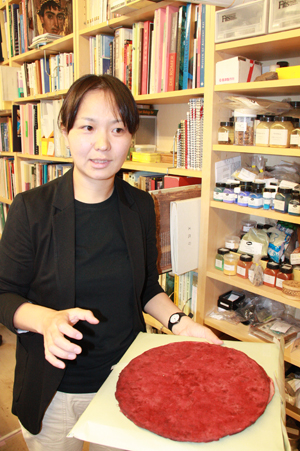

A variety of pigment samples are preserved in the lab.

Prof. Taniguchi participates as a lecturer in the Project for the Grand Egyptian Museum Conservation Center conducted by JICA. Here she explains the painted replica samples created by the trainees.

Prof. Taniguchi has performed a variety of analyses on more than 300 tiny samples (fragments) taken from about 50 stone cave murals. The results showed that walnut oil or poppy-seed oil were used in some of the murals. An "oil painting" can be defined as a picture drawn with colors in which drying oils (drying refers to the quality of something that hardens when exposed to air) were used as a material for fixing the pigments in place (an agglutination agent). Based on this definition, the Bamiyan murals can be categorized as "oil paintings." Researchers found remains of straw, wood fragments, and rope from the fragments of the rammed-earth walls around the destroyed large Buddhas. The results of radioactive carbon-dating based on these organic materials suggest that the large Buddhas of Bamiyan were created in the 5th to 7th century, and that the murals were created in the 5th to 10th century. The murals that have been identified as oil paintings were created in the 7th to 9th century. The oldest example known up to that point to use drying oil for agglutination had been the painted wooden sculpture of Christ's crucifixion, located at a church on the island of Gotland in Sweden, which dates back to the end of the 12th century. In other words, this discovery pushes the origins of oil painting back a full five centuries, and shifts them from Europe to Asia. This discovery was selected as one of the Top 10 Discoveries of 2008 by Archaeology, a publication of the Archaeological Institute of America.

Prof. Taniguchi graduated from the College of Humanities at the University of Tsukuba and studied the conservation of cultural properties at the Tokyo University of the Arts Graduate School. After spending time at several research institutes both in Japan and abroad, she joined the faculty of the University of Tsukuba in April 2008. She says the starting point for her interest in this field was Jomon pottery. She was drawn to the diversity and enchanting quality of Jomon art. In the Jomon period, red dye artificially made using iron bacteria was already in use, and surprisingly, a fascinating artistic culture was already being developed. At that time, materials in the soil and earth were already being used, of course, as were items obtained through trade. If we understand the chemical composition of these kinds of materials, we are able to infer something about the culture of that time, as well as the level of techniques and lifestyle patterns that were in play. We can even take it one step further to explore fundamental questions about where the Japanese people, as well as their folk customs and culture, came from.

In addition to using radiocarbon dating for her research, Prof. Taniguchi also uses synchrotron radiation facilities such as SPring-8, electron microscopes, and cutting-edge analysis techniques. She is also working to propagate preservation and repair techniques for ancient colored cultural assets such as those found in Egypt. She has conducted fieldwork in a number of countries and regions including Afghanistan, India, Egypt, China, Cuba, and Syria, and plans to continue doing joint research with researchers and people from many regions, taking advantage of the noteworthy resources of University of Tsukuba.

Using the equipment at SPring-8, researchers perform an X-ray absorption fine structure analysis on blue beads from Syria.

Article by Science Communicator at the Office of Public Relations