TSUKUBA FUTURE

#069 Interdisciplinary Research Inspired by the Aroma of Plants

Assistant Professor KINOSHITA Natsuko, Faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences

We would usually be surprised to hear about plant communication because we believe that communication is limited to animals. Plants send and receive signals to communicate amongst themselves, as well as with insects and other organisms. Although Prof. Kinoshita's interest was piqued by plants' latent ability to communicate via aromatic substances, she is actually a member of the applied entomology research group.

At the time Prof. Kinoshita took up her post at the University of Tsukuba, she had been considering changing her research theme. In graduate school she had researched how plants react, at the molecular level, to salt and dehydration related stress. At Rockefeller University she studied plants' dynamic reactions to stress. Prof. Kinoshita inadvertently became interested in the science of smells and odors because there are few plant researchers at Rockefeller University and she was surrounded by numerous people researching the neurophysiological connections of the sense of smell. This was her trigger to research smell-based plant communication when she took up her new post, but she chose to join the Applied Entomology and Zoology Research Lab, in which the main themes of research include parasitic insects which are natural enemies of agricultural pests, the physiology of mites which are sanitary pests, research into defense systems based on immunity in which insects protect themselves from pathogens and natural enemies, and chemical ecology. Chemical ecology is research into communication among insects and between insects and plants using chemical substances. Prof. Kinoshita's interest in plant smells led to her decision to move across to research into communication between plants that have been damaged by insects.

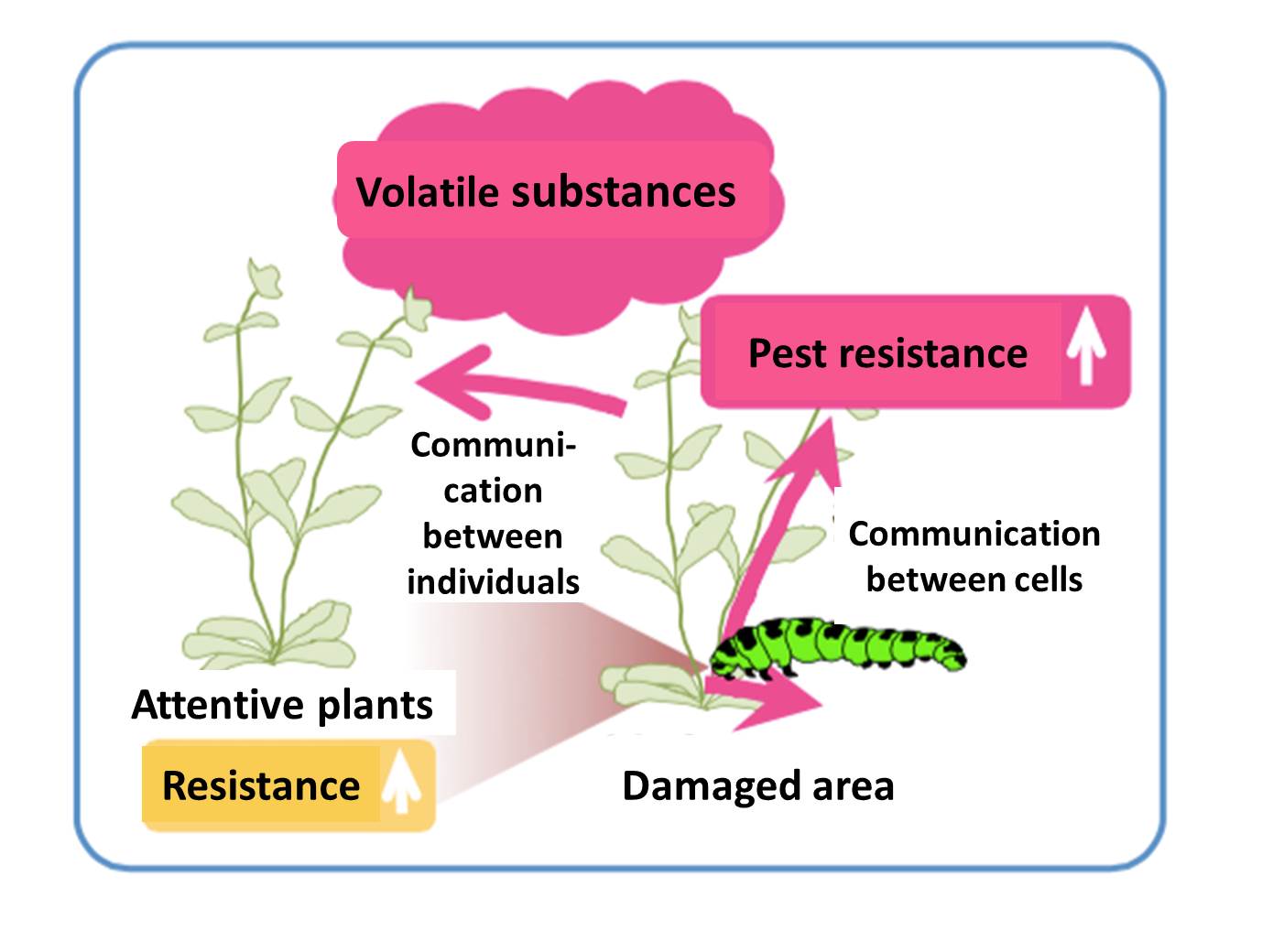

Plants emit a certain signal when they are being eaten by insects. In human terms this would be shouts of "Ah, I'm under attack, ouch, it hurts." Both the membrane and cytoplasm of plant cells have receptors which pick up these signals in animals only the membrane has these receptors. This same signal emission mechanism is not triggered only when the plant is being eaten Prof. Kinoshita's research showed that it is also used in conditions of water and nutrition stress. The emission of signals by stressed cells to the other cells means that the plant can take measures to deal with the stress and try to bolster its preparedness. On the other hand, stress induced by disease or insect damage is communicated to neighboring plants via the smell of volatile substances. This is a warning signal that enemies are in the area. This is described by some researchers as plants sending out a "bouquet." However, these signals are also sent out for the plant's own benefit. For example, the odor emitted by a plant being attacked by spider mites attracts phytoseiid mites which are natural enemies of spider mites. In another example, when under attack, tobacco plants produce greater quantities of nicotine which is harmful to insects. What is more, neighboring plants which have detected a "bouquet" then emit the same odor and can thus attract phytoseiid mites to pre-empt an attack. In other words, the plant is "attentive" to what is going on nearby and can thus make preparations. We also know that plants which have received signals emitted by a diseased plant reinforce their immune systems, which are responsible for resisting pathogens.

Plants being fed upon emit warnings and share information!

As a plant molecular biologist, Prof. Kinoshita's field of interest is the plant, not the signal recipient natural enemy. If details of how plants react to detected bouquets are understood, then perhaps their findings could be applied to farms and plant factories. The possibilities are endless, but for the moment Prof. Kinoshita's day to day task is basic research using the model plant known as Arabidopsis and diamondback moth larvae which feed off it. Prof. Kinoshita is also participating in an on-campus joint research project into rice plant cesium absorption, which has been investigating the possibility of changing fertilizer balance in order to prevent cesium from being absorbed, and also trying to make plants absorb cesium selectively.

Prof. Kinoshita gives specialist subject lessons in English to students and her lab is a multinational contingent who hail from the U.S., Russia and Japan. In this way not only the research themes but also the education and research environment all transcend borders.

A multinational lab team

Article by Science Communicator at the Office of Public Relations